Learn More About Our Categories

Caregiver Guidance

Information and tools for getting support, advocating and staying organized.

All Resources

Search for Resources

Clear all filters

Caregiver Guidance

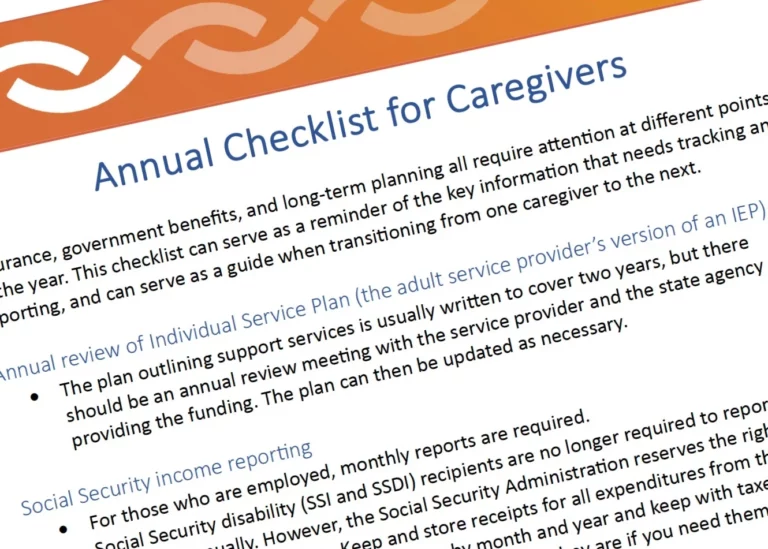

Keeping Important Paperwork Up to Date: A Checklist for Caregivers

Caregiving is a full-time job that includes not just keeping people fed, safe and happy, but making sure that financial, legal and social service supports stay in place.

Insurance, government benefits, and long-term planning all require attention at different points in the year. This checklist can serve as a reminder of the key information that needs tracking and reporting, and can serve as a guide when transitioning from one caregiver to the next.

Annual Review of Individual Service Plan (the Adult Service Provider’s Version of an IEP)

The plan outlining support services is usually written to cover two years, but there should be an annual review meeting with the service provider and the state agency providing the funding. The plan can then be updated as necessary.

Social Security Income Reporting

For those who are employed, monthly reports are required.

Social Security disability (SSI and SSDI) recipients are no longer required to report expenses annually. However, the Social Security Administration reserves the right to audit expenses at any time. Keep and store receipts for all expenditures from the Representative Payee account. Organize by month and year and keep with taxes for at least seven years. This way you know exactly where they are if you need them.

Annual Probate Reports for Guardians (varies by state)

The date for reporting varies from state to state because the laws governing guardianship are different. Often it’s on the anniversary of the date when guardianship was granted by the court.

Many states require a yearly expense report, so it’s helpful to have an organization system for keeping and filing receipts and expenses.

Letter of Intent

A Letter of Intent is a document many families include in their estate plan to help the next generation of caregivers understand the key supports and preferences of the disabled adult. (Learn more about letters of intent from Special Needs Financial Planning).

Everyone’s needs and preferences change over time. Review and update yearly to ensure the Letter of Intent reflects the most recent priorities in the life of the autistic person served by the letter.

Annual Medical Appointments

parent(s)/caregiver(s)

autistic adult

spouses, partners, and siblings, too

annual physical with PCP

dentist

optometrist

gynecologist/urologist

Medication Renewals and Refills

Some prescriptions require a new prescription from a provider on a monthly basis (example: stimulant medications). For many other medications, prescriptions can be written to allow refills for longer periods (up to a year). Schedule in-person visits so that they take place before prescriptions expire.

Open Enrollment for Private Health Insurance

Keep track of enrollment periods, as dates and opportunities vary. Some employers offer open enrollment at the end of the calendar year, while others may offer this window at the beginning or end of a quarter, such as in July or September.

Medicare and Medicaid renewal. Medicare always rolls over at the end of the year. For the most up-to-date information about coverage, contact them directly at 1-800-MEDICARE.

See also our resources on insurance:

Differences Between Medicare and Medicaid

Finding Local Help with Autism Insurance Coverage

Insurance: Turning 26

Communicating About Pain

Autistic people often find that when they feel pain they can’t explain it or locate the source of it as easily as most neurotypical people can.

In the past, some clinicians believed autistic people do not feel pain the way neurotypical people do, which was to say they thought that people who could not verbally communicate about their pain not feeling pain. We now know this isn’t true. Autistic people often find that when they feel pain they can’t explain it or locate the source of it as easily as most neurotypical people can.

Some autistic people may be more sensitive to pain than their neurotypical peers. This can be especially true for girls and women who have autism. This is why talking about pain is one of the most critical conversations to have with a new provider, and it should happen before the first physical exam.

Behaviors that may indicate pain in non-verbal adults

It’s sometimes hard to distinguish between behaviors that indicate pain and those that seek to communicate another problem. Some of the common pain related behaviors are:

Aggression

Running, pacing, bolting

Jumping, stomping, thrashing

Self-injury, sometimes, but not always at the source of the pain (such as banging/hitting head when having GI pain)

Subtle or strong pinching or grabbing body part that source of pain

Sudden, exaggerated repetitive actions, like hand flapping or throat scratching

Twisting or irregular motions/positions to make accommodations for discomfort

Screaming

Ingestion (e.g. overeating, quickly ingesting food and drink, food avoidance, vomiting, mouthing or eating non-food items)

Crying

Withdraws or becomes very still

Checklist for talking to a clinician about pain

It can be helpful to carry a list of pain-related concern to appointments. It might include:

It hurts when people touch me without asking first.

The thought of feeling pain makes me very nervous.

If something will cause pain, please tell me ahead of time.

If something will cause pain, please give me medicine or treatment to help it hurt less.

Pain scares me.

I don’t like needles and need to know if there will be shots or blood draws that might be painful

Using a Pain Scale

If a medical appointment involves addressing pain as a problem or symptom, it may be helpful to use a tool known as a pain scale. Pain scales give patients a way to self-report their pain in a way that helps clinicians make an accurate evaluation and diagnosis of underlying health issues.

There are several kinds of pain scales:

One type of pain scale involves patients assigning a number between 1 and 10 to . One would be “no pain,” and 10 would be the worst pain imaginable.

A non-verbal pain scale for adults may also be used to help communicate about and identify the source and severity of pain. Karen Turner, OT and Patient Navigator at Massachusetts General Hospital, explains:

Karen Turner, OT, is a Patient navigator at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston

The Massachusetts General Hospital Patient Accommodations Care Plan is useful communication tool that allows patients and families to document important conditions and behaviors that clinicians should know, including pain.

More information

Neuroscience News on People with Autism Experience Pain at a Higher Intensity

Recent research on autism and pain in adults.

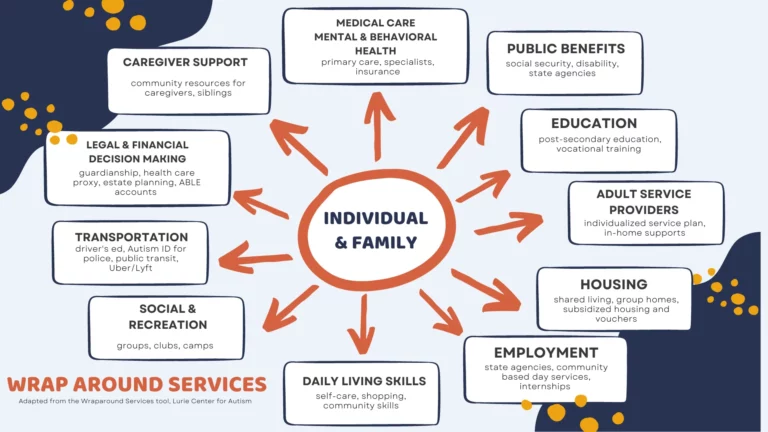

Family Support and Wraparound Services

Many providers have people on staff who can help families understand and navigate a variety of health and community services.

Some medical practices and hospitals have family support clinicians or clinical social workers that can help patients with sensory needs or communication impairments identify support services within the community. Family support clinicians make referrals, collaborate, problem-solve, and connect to supports to help autistic adults and caregivers successfully navigate services across the lifespan. These “wraparound services” address important needs across the lifespan like medical/health concerns, special education, social/behavioral supports, public benefits, legal/financial advice, housing, vocational training, transportation, etc.

Not every medical practice serving adults has a support clinician, but caregivers and self-advocates can encourage the practice to create such a resource. Support clinicians not only improve the lives of autistic adults and their caregivers, but they also ease the workload of the entire practice by ensuring whole-life health for all patients and their caregivers.

Julie M. O’Brien, MEd, LMHC, a Family Support Clinician at the MGH Lurie Center for Autism, helps to educate and support families by identifying a range of home- and community-based supports and resources by age and stage of life. She serves as the liaison between the patients’ provider and parents/guardians/families, and points them in the right direction.

Useful links to find out more about sites and organizations that can help with wraparound services.

Housing

Autism Speaks Resource Guide

Autism Housing Network

Autism Housing Pathways

Education

Postsecondary Education Toolkit

Independent Living and Life Planning

LifeCourse Tools

AANE LifeNet independent Living Support Program

Autistic Self Advocacy Network

Employment

NEXT for Autism

Service Providers

Council of Autism Service Providers

Autism Speaks Directory of Service Providers

Legal & Financial Issues

Autism Advocacy Law Center

Guide for a Letter of Intent

Financial Planning Toolkit

Social Connections & Supports

AANE Online Support and Discussions

Support for Families of Those with Profound Autism

Profound Autism Alliance

How is Autism Different in Women?

Autism is a diverse condition that affects individuals of all genders. Although it is still more commonly diagnosed in males, recent research suggests that the disparity is shrinking as awareness of how autism presents in females increases.

This article is based on a LurieNOW article by Dr. Alyssa Milot Travers, a licensed psychologist at the Lurie Center for Autism with specific expertise in women on the autism spectrum. Dr. Travers is also an Instructor in Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

Autism is a diverse condition that affects individuals of all genders; the overall prevalence estimate of autism in the U.S. is one in 36 children. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as of March 2023 about 4% of boys and 1% of girls age 8 years have autism.

Although an autism diagnosis occurs more often in men than in women, recent research suggests that autism in women may be both underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed. Recognizing and understanding how autism presents in women is crucial for accurate diagnosis, appropriate support, and targeted interventions. The evolving understanding of gender differences in autism is dismantling the notion that autism is more or less a “male condition.”

Gender identity in autism research

The majority of autism research in recent decades has focused on cisgender individuals, or those who have a gender identity that matches their sex assigned at birth. The most current research reveals that gender diversity is more common in autistic people than in their neurotypical peers. Consequently, there is a slow but distinct shift toward including gender diversity in autism research, which will provide a more accurate representation of all autistic individuals. The current knowledge of the female subtype of ASD is based on research of cisgender women.

Outward signs: Special interests and repetitive behaviors

Restricted interests and repetitive behaviors occur in autistic men and women; however, the nature of these behaviors can differ. Traditionally, clinicians have been trained to recognize stereotypical male-associated restricted interests, such as transportation, dinosaurs, or space. In contrast, autistic women may develop interests that are more closely aligned with societal norms, such as animals, art, celebrities, or literature.

This divergence can contribute to the misconception that women with these types of restricted interests are simply displaying enthusiastic hobbies rather than autistic traits. Repetitive patterns of behavior in women may manifest as classic autistic behaviors like rocking or hand/finger movements. However, they may also appear as behaviors not necessarily associated with autism, such as perfectionistic tendencies or restrictive patterns of eating/eating disorders.

Impediments to an ASD diagnosis: Overshadowing, masking, and camouflaging

Based on behavioral history, women may be more apt to receive diagnoses such as anxiety, mood disorders, learning disorders, and/or eating disorders rather than autism. This phenomenon is called diagnostic overshadowing, which occurs when a person’s symptoms are attributed to a psychiatric problem versus an underlying medical condition or a developmental delay such as autism. This can complicate the diagnostic process, as the focus may be on managing these secondary conditions rather than recognizing the underlying autistic traits.

Autistic women are also more likely to develop compensatory strategies to mask their challenges. For example, women often have stronger social imitation skills and the ability to mimic social behavior compared to men. Due to their social foundation, girls may develop one or two close friendships, helping them absorb social rules and norms. Their strong social interest may lead them to “camouflage” or compensate for social understanding and communication challenges, making these vulnerabilities difficult to detect in everyday interactions or larger classroom or employment settings. As a result of these differences, women are often more likely to be diagnosed later in life, if at all.

The Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network provides useful information and resources for gender-diverse autistic individuals.

For diagnostic resources, see our article about seeking an ASD diagnosis as an adult.

Recommended Reading and Viewing

For women:

Camouflage: The Hidden Lives of Autistic Women by Dr. Sarah Bargiela

22 Things a Woman with Asperger’s Syndrome Wants Her Partner to Know by Rudy Simone

The Autistic Brain: Exploring the Strengths of a Different Kind of Mind by Temple Grandin

Odd Girl Out: An Autistic Woman in a Neurotypical World by Laura James

From the American Autism Association: 5 TedX Talks from Women with Autism

For caregivers:

A Guide to Mental Health Issues in Girls and Young Women on the Autism Spectrum: Diagnosis, Intervention and Family Support by Dr. Judy Eaton

Girls Growing Up on the Autism Spectrum: What Parents and Professionals Should Know About the Pre-Teen and Teenage Years by Shana Nichols with Gina Marie Moravcik and Samara Pulver Tetenbaum

For partners of autistic adults:

The Other Half of Asperger Syndrome: A Guide to Living in an Intimate Relationship with a Partner Who is on the Autism Spectrum by Maxine Aston

Autism and Grief

The transitions surrounding loss are some of the most unrecognized and difficult ones for autistic people. Like many deeply emotional events, autistic people often process the separation differently.

Processing loss

The transitions surrounding loss are some of the most unrecognized and difficult ones for autistic people. Like many deeply emotional events, autistic people often process the separation differently. At the same time, many autistic people take comfort from the rituals that accompany death in many cultures. Events such as wakes, funerals, memorial services, and burials can be helpful transition points that acknowledge loss and give it context. Even for those who cannot or choose not to participate fully, these events can encourage conversations about the person who has died. For more advice and ideas, including information about how many religions address death, visit the award-winning Autism and Grief Project.

Signs of grieving

Autistic people may not react to loss or express grief in real time. A delayed reaction might appear week or months later and take the form of:

unusual behavior changes such as dysregulation, mood swings, and aggression

social and emotional withdrawal

spurts in stereotypy or repetitive behaviors

increases in creative activities such as drawing, painting, or collecting.

Coping with loss

One of the biggest challenges that can come with loss is the change in routine. When it’s possible to plan for the grieving process, it can be helpful to update or create new routines that can replace or fill the inevitable void. It’s also useful to remember that everyday tasks can take on added meaning when done with or for someone beloved. Creative ways for an autistic adult to help remember a loved one can include:

designing printed memorial cards

creating one or more photo and/or memory books (a portable one that can be carried in a backpack or the car can be helpful when away from home)

assembling a slide show that can be watched on a phone or tablet

creating a drawing or collage, or establishing a routine around making these types of art projects

establishing a dedicated place to collect and display mementos that recall positive memories

recreating fond food memories by making or eating special meals.

Author Susan Senator, parent of an autistic adult, has advice about How to Help an Autistic Person Process Grief and Loss in Psychology Today.

Losing our beloved Poppa was traumatic, and he insisted that he did not want a funeral. The lack of closure was very difficult for our autistic adult son, who misinterpreted the wish for no formal services as a sign that his grandfather died from a broken heart. He would talk of little else for months, until we set aside times together to spread some ashes in a few of his Poppa’s favorite places.

— Sarah T., parent of an autistic adult

The Formal Diagnostic Criteria for Autism

When a clinician makes a formal diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder, they use the criteria laid out in the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Volume V, 2013. It reads as...

When a clinician makes a formal diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder, they use the criteria laid out in the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Volume V, 2013.

It reads as follows:

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Diagnostic Criteria 299.00 (F84.0)

Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive; see text):

Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

Specify current severity: Severity is based on social communication impairments and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior (see Table below).

Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive; see text):

Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypies, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat same food every day).

Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g., strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests).

Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

Specify current severity: Severity is based on social communication impairments and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior (see Table below).

Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities, or may be masked by learned strategies in later life).

Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder frequently co-occur; to make comorbid diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability, social communication should be below that expected for general developmental level.

Note: Individuals with a well-established DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified should be given the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Individuals who have marked deficits in social communication, but whose symptoms do not otherwise meet criteria for autism spectrum disorder, should be evaluated for social (pragmatic) communication disorder.

Specify if: With or without accompanying intellectual impairment

With or without accompanying language impairment

Associated with a known medical or genetic condition or environmental factor (Coding note: Use additional code[s] to identify the associated medical or genetic condition.)

Associated with another neurodevelopmental, mental, or behavioral disorder (Coding note: Use additional code[s] to identify the associated neurodevelopmental, mental, or behavioral disorder[s].)

With catatonia (refer to the criteria for catatonia associated with another mental disorder, pp. 119-120, for definition) (Coding note: Use additional code 293.89 [F06.1] catatonia associated with autism spectrum disorder to indicate the presence of co-morbid catatonia.)

Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder

Diagnostic Criteria 315.39 (F80-.89)

Persistent difficulties in the social use of verbal and nonverbal communication as manifested by all of the following:

Deficits in using communication for social purposes, such as greeting and sharing information, in a manger that is appropriate for the social context.

Impairment of the ability to change communication to match context or the needs of the listener, such as speaking differently in a classroom than on a playground, talking differently to a child than to an adult, and avoiding use of overly formal language.

Difficulties following rules for conversation and storytelling, such as taking turns in conversation, rephrasing when misunderstood, and knowing how to use verbal and nonverbal signals to regulate interaction.

Difficulties understanding what is not explicitly stated (e.g., making inferences) and nonliteral or ambiguous meanings of language (e.g., idioms, humor, metaphors, multiple meanings that depend on the context for interpretation).

The deficits result in functional limitations in effective communication, social participation, social relationships, academic achievement, or occupational performance, individually or in combination.

The onset of the symptoms is in the early developmental period (but deficits may not become fully manifest until social communication demands exceed limited capacities).

The symptoms are not attributable to another medical or neurological condition or to low abilities in the domains of word structure and grammar, and not better explained by autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder), global development delay, or another mental disorder.

Reprinted with permission from American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Copyright © 2013. American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. Permission from the APA is required to reproduce DSM-5 Criteria and any Related Tables.

More information from AAHR

Getting an Autism Diagnosis as an Adult

The Language of Autism

How is Autism Different in Women?

Sibling Relationships

Communication is key to building healthy relationships and smooth transitions among family members.

Brothers and sisters, or siblings, are often key players for autistic adults and their caregivers, especially during transitional times. Research shows that autistic people who have siblings develop better social skills as well as a built-in resilience.

If an autistic person has more than one sibling, they are likely to have a different relationship with each. For example, some siblings may be able to provide strong emotional support, while others may be better at helping with, or taking on, decisions about finances and care. These roles can evolve across the lifespan, so it’s important that siblings try and maintain positive communication — not only with the autistic adult, but with one another.

Unique family dynamics

As in any family, sibling relationships change over time, but there can be unique challenges for both the autistic adult and their siblings during different stages of life. For example, older siblings might feel a sense of responsibility toward their autistic sibling and feel tentative about building a life outside the family unit. Younger siblings gain independence and develop skills and relationships that lead them to surpass their older, developmentally delayed autistic sibling. When this happens, autistic adults may struggle with feeling abandoned or jealous when a younger sibling moves out, gets married, or has children, while siblings in turn can feel guilty about becoming more independent.

Navigating sibling milestones

The goal for caregivers is to encourage the autistic adult to accept and adapt to the changes in routine and family structures, to ensure that siblings feel empowered to build independent lives while maintaining family connections. It’s productive to have conversations with the autistic adult about sibling life milestones in advance, to the extent that it’s possible. For example, when siblings prepare to leave home, caregivers can address:

how daily routines will change

when siblings will come home or when family will visit them

whether a sibling’s space or room will stay the same or be used for something else

ways siblings can communicate regularly (email, letter, video call).

Caregivers can help siblings by encouraging and supporting their life choices outside of the family home and communicating regularly about any changes in care, employment supports, and living arrangements with their autistic sibling. Keeping siblings informed about specific and general caregiver responsibilities gives them a chance to consider what role they may feel comfortable playing during their autistic sibling’s later years.

Resources for siblings

As attuned as caregivers can be to the needs of all of their children, parents who did not grow up with an autistic sibling can’t always empathize or understand the impact of autism on siblings. For most siblings, autism has punctuated their entire childhood. Siblings often benefit from talking with other siblings of autistic people or speaking with a therapist familiar with the dynamics of families touched by autism.

Because anxiety and depression are more common among siblings of autistic people, it’s important to assure that support and care are readily available. For families of people whose autism includes challenging behaviors, Autism Speaks has a guide for siblings and a Q&A that addresses some of those issues.

Sibling roles as caregivers age

Just as setting expectations and arranging for visits and regular contact is key when siblings first leave home, communication becomes increasingly important as caregivers and autistic adults get older. Family gatherings and holidays can be stressful for siblings if it is assumed they will replicate childhood rituals or vacation in the same place every year. Siblings can assist in skillfully introducing new activities alongside longtime family traditions, which serves to lighten the load on caregivers and prepare for transitions of care.

Another key consideration for siblings is how to plan for the time when parents, caregivers, or guardians can no longer provide care or support for the autistic adult. This is especially challenging when an autistic adult still lives at home. Siblings need to understand what caregivers do day-to-day long before this transition occurs, so that they are prepared to make decisions about care and support when the time comes.

Some things to consider:

How well do the siblings get along with their autistic sibling?

How do the neurotypical siblings get along with each other?

Have siblings been made aware of financial arrangements for their autistic sibling?

Are siblings prepared to advocate for the autistic adult?

Do siblings understand the medical needs of the autistic adult?

Caregivers can create opportunities to discuss and answer these questions and incorporate them into plans as they approach later transitions.

Learn more

AAHR article on Family Support and Wraparound Services

The Profound Autism Alliance has a Sibling Action Network

Autism Speaks: A Sibling’s Guide to Autism

Autism Speaks Q&A: Supporting Siblings of Autistic Children with Aggressive Behaviors

How to Bring Adult Siblings Into an Autistic Brother’s Life by Susan Senator in Psychology Today

The Sibling Support Project has resources and trainings for siblings of people with developmental disabilities

Autism Spectrum News on Adult Sibling Support

The Autism Science Foundation has a site with multiple resources for siblings, Sam’s Sibs Stick Together

Navigating Grief and Loss: A Guide for Siblings of people with IDD

Next steps: Starting the Conversation: Future Planning and Siblings of People with IDD.

Types of Mental Health Providers

When seeking mental health care - therapy, diagnoses or medication - it's helpful to know which providers offer which kinds of care.

Psychiatrists are licensed physicians (MDs or DOs) that evaluate and diagnose mental health conditions, prescribe and monitor medications, and provide therapy.

Psychiatric or mental health nurse practitioners evaluate and diagnose mental health conditions, prescribe and monitor medications, and provide therapy. Similar to a psychiatrist, they are also qualified to prescribe and monitor medications (regulations vary by state).

Psychiatriatric pharmacists/psychopharmacologist (PharmD) are advanced-practice pharmacists who specialize in mental health care, including prescribing and monitoring medications.

Psychologists can evaluate and diagnose mental health conditions, assess patients’ mental states, emotional processes, and behavior, and provide therapy. Clinical psychologists with specialized training can also complete more detailed psychological and neuropsychological assessments.

Clinical neuropsychologists (PhD) are clinical psychologists with specialized training who conduct detailed neuropsychological evaluations, including assessment of general intellectual abilities, language, attention, memory, motor skills, and emotional and behavioral functioning.

Licensed professional counselors (LPCs) are licensed mental health counselors who provide mental health and substance use care.

Licensed marriage and family therapist (LMFTs) are licensed to evaluate, diagnose, and treat mental and emotional disorders within the context of marriage, couples, and family systems.

Licensed clinical alcohol & drug abuse counselors (LCADACs) provide substance use counseling and diagnosis, prevent, treat, and ameliorate psychological problems, emotional conditions, or mental conditions of individuals or groups.

Clinical social workers (MSW) provide a range of social work services, including treatment for mental illnesses.

Licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs) are licensed clinical social workers who can evaluate, diagnose, and treat patients’ mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders under the continued clinical supervision of an LICSW.

Licensed independent clinical social workers (LICSWs) are licensed professionals who independently practice clinical social work, including the ability to evaluate, diagnose, and treat patients’ mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders. LICSWs work to restore or enhance patients’ social and psychosocial functioning.

More information:

The National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI) offers help finding mental health providers and links to support groups.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration offers 24-hour referral and support.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline800-662-HELP (4357)TTY: 800-487-4889

All talk of and thoughts about suicide are serious.

People facing a mental health crisis or thoughts of suicide can call or text 988 from any phone.

For more help and information contact Lifeline.

Deaf and hard of hearing adults can access 988 resources by using the “ASL now” button on the 988 Lifeline site, or by dialing 800-973-8255 with a phone capable of making video calls

Clinical Care for Autistic Adults

Clinical Care for Autistic Adults is led by nationally recognized experts, with extensive expertise caring for adults with autism.

A course for medical professionals

Given the unique needs of autistic adults, many clinicians find themselves underprepared for the complexity of diagnoses, the diversity of presentations, and the coordination of care. Clinical Care for Autistic Adults is led by nationally recognized experts, with extensive expertise caring for adults with autism.

Clinical Care for Autistic Adults is designed for clinicians who currently provide care to autistic adults or are preparing to welcome autistic patients into their practice. Its goal is to empower clinicians to provide personalized care for autistic people and their families. Clinicians who complete this course will able to:

Recognize the range of needs that autism presents across spectrum and age

Examine the gaps that exists for support of adult autistic patients

Identify key players in the ongoing support of autistic patients throughout the adult lifespan

Apply best practices and strategies to better support patients during adult primary and specialist visits, screenings, and medical procedures

Develop and utilize communication protocols to increase effectiveness of transitions of care

See the course description: Clinical Care for Autistic Adults

Share this code with providers to give them direct access to the course:

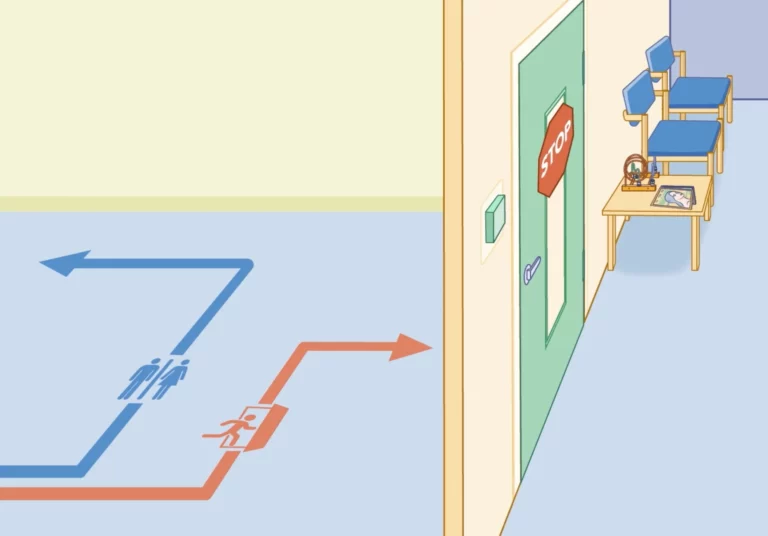

Medical Facilities for After-Hours Care

Health care problems often arise outside of primary care physican’s (PCP) regular office hours. It’s good to know what other options are available for medical care if you become sick or injured with a non-life-threatening condition after hours or if you’re traveling away from home.

When health care problems arise at night, on weekends, or away from home, it’s good to know what the options available for after-hours medical care. The first step is to call your primary care physician’s (PCP) office. They will likely have instructions on their voicemail or their answering service will connect you to a clinician on call.

If you choose to, or are directed to care at an outside medical facility, it is helpful to have a clear idea about what a particular facility can or cannot treat. When possible, call ahead to find information about scope of services, hours, potential wait time, and types of insurance accepted. Some walk-in clinics and urgent care facilities have online appointment and check-in procedures that allow patients to make appointments for the best or first-available time. Be sure to bring an Emergency Go Bag for extended or unexpected wait times.

It’s also helpful to understand the distinction between the scope of care and types of providers that a walk-in or urgent care center may offer in comparison to an emergency department. Depending on state requirements, for example, a walk-in clinic or an urgent care center may not necessarily have physicians, mental health clinicians, or radiologists on site.

Types of medical care facilities outside of a PCP office

Walk-in clinic. Provides non-urgent/non-emergency basic medical care for minor conditions such as colds, flu, cuts, or skin conditions. Many urgent care centers (see below) take walk-ins.

Urgent care center. A step up in care from a typical walk-in clinic, urgent care centers also treat non-urgent/non-emergency illnesses or injuries along with conditions that may require laboratory and x-ray services.

If a health care problem is determined to be a true medical emergency, the walk-in or urgent care staff will refer the patient to an emergency department. Transfer by ambulance will be assessed depending on the urgency of the situation.

Emergency department (ED) (often called emergency room). The designated part of the hospital that provides unscheduled, 24/7 care for serious illnesses, accidents, or mental health crises. EDs stabilize and treat patients with medical emergencies. If further care is required, then a patient may be admitted to the hospital.

Planning for Medical Emergencies

Everyone—autistic people and neurotypical people—can benefit from planning for medical or mental health emergencies.

Be ready: Make a 'Go Bag'

Emergencies are easier to handle if information and supplies are at the ready. Keeping a Go Bag near the door or in the car can help.

The Go Bag – a printable list of things to have on hand to help prepare for emergencies

Start by calling the PCP

Everyone—autistic people and neurotypical people—can benefit from planning for medical or mental health emergencies. If a trip to the emergency department (ED) is necessary, you’ll want to alert your primary care provider’s office (another person in the household can make this call as necessary). It’s especially helpful to request that the PCP call ahead and let the ED or hospital know that an autistic patient is on the way and they can share any pertinent information that can be helpful for your care.

Make a call tree

Another key part of the plan is to create a call tree that includes someone in the circle of support who can contact others who should be alerted to the emergency. This information should be clearly displayed in a prominent position in your home. This is especially important for first responders-police, fire, and EMS – in case you are alone during an emergency. The call tree contacts can include service provider or group home staff, neighbors who can assist with caring for others in the family, and extended family.

Register with the local police

Most local police departmetns have a way of registering citizens with special health needs. If there are details they should know about how autism presents in you or the adult in your family take a moment to communicate about those concerns. For example, some people panic and hide when they hear sirens, see someone in uniform, or even hear the doorbell.

Calling 911

Most clinicians’ offices direct people in crisis to the local emergency department or urgent care center. If calling 911 is the best or only option, clearly state to the dispatcher that the patient is a person with autism and let them know about any communication or behavioral challenges that might be misunderstood. Many first responders are trained to interact with autistic people but many are not – it’s important to know ahead if time if local police, fire, and EMS are trained in working with the autistic community. Autism Speaks has a guide for first responders that can be shared with local public safety organizations, including information for dispatchers. In addition, there are several programs that train first responders to safely interact with autistic people, including Autism Alert and Autism Risk and Safety Management.

Tips for interacting with first responders

Whether an emergency occurs in the home or out in the community, an autism ID can be useful. It can be a simple card with details that are specific to the individual and can help avoid misunderstandings in stressful situations. Caregivers can share an ID card or self-advocates can carry them and share as necessary.

The card be shared with first responders or with staff and clinicians in emergency departments, urgent care, and hospitals. There are Medicalert IDs for autism and also sites that can create an autism ID for a fee. This one was created using a free site called Canva:

A sample identification card that outlines what strategies autstic people can use to communicate in an emergency

Mental health emergencies

When there’s a mental health emergency, think carefully about what the goal is for taking someone to the Emergency Department. Dr. Robyn Thom, a psychiatrist at the MGH Lurie Center for Autism, discusses expectations for a mental health care visit to the Emergency Department:

Dr. Robyn Thom on things to consider when going to the emergency room for a mental health emergency.

A 3×5 identification card to print and use for communicating in an emergency

Medical Specialists and What They Treat

Many autistic adults and caregivers are familiar with the type of medical care that specialists, such as neurologists and gastroenterologists, provide for co-occuring health conditions. We’ve compiled this list of specialists so that autistic adults are familiar with more types of clinicians that treat health issues that may arise across the lifespan.

Allergists or immunologists treat allergies, asthma, and immunologic disorders, including primary immunodeficiencies.

Anesthesiologists administer anesthetics and analgesics for pain management pre-, during, and post-surgical procedures.

Cardiologists treat conditions related to the cardiovascular system (heart and blood vessels).

Dermatologists treat conditions related to the skin, hair, and nails.

Endocrinologists treat hormone-related conditions.

Gastroenterologists treat conditions related to the digestive system.

Geriatric physicians/geriatricians treat medical and psychological conditions associated with aging.

Hematologists treat blood disorders, including leukemia.

Infectious disease specialists treat conditions related to infections that are contagious.

Nephrologists treat conditions related to kidney function.

Neurologists treat conditions affecting the nervous system (brain, nerves, and spine).

Medical geneticists diagnose and treat genetic (inherited) conditions.

Obstetrician/gynecologists (OB/GYNs) treat conditions related to female reproductive health, including pregnancy, childbirth, menstruation, and menopause.

Oncologists specialize in diagnosing and treating cancer.

Ophthalmologists treat conditions related to the eyes.

Otolaryngologists or “ear, nose, and throat” clinicians (ENTs) treats conditions involving the throat, tonsils, sinuses ears, mouth, head, and neck.

Podiatrists treat conditions affecting feet, ankles, and related structure of the legs.

Proctologists or colorectal surgeons specialize in diseases and conditions of the lower digestive tract, including the anus, colon, and rectum.

Pulmonologists treat conditions related to breathing functions of the lungs and heart.

Rheumatologists treat rheumatic and autoimmune conditions affecting the bones, joints, tendons, and muscles.

Urologists treat conditions of the urinary tract and also care for male reproductive health.

For a more comprehensive list of specialists go to the HHP List of specialists.

Allergists or immunologists treat allergies, asthma, and immunologic disorders, including primary immunodeficiencies.

Anesthesiologists administer anesthetics and analgesics for pain management pre-, during, and post-surgical procedures.

Cardiologists treat conditions related to the cardiovascular system (heart and blood vessels).

Dermatologists treat conditions related to the skin, hair, and nails.

Endocrinologists treat hormone-related conditions.

Gastroenterologists treat conditions related to the digestive system.

Geriatric physicians/geriatricians treat medical and psychological conditions associated with aging.

Hematologists treat blood disorders, including leukemia.

Infectious disease specialists treat conditions related to infections that are contagious.

Nephrologists treat conditions related to kidney function.

Neurologists treat conditions affecting the nervous system (brain, nerves, and spine).

Medical geneticists diagnose and treat genetic (inherited) conditions.

Obstetrician/gynecologists (OB/GYNs) treat conditions related to female reproductive health, including pregnancy, childbirth, menstruation, and menopause.

Oncologists specialize in diagnosing and treating cancer.

Ophthalmologists treat conditions related to the eyes.

Otolaryngologists or “ear, nose, and throat” clinicians (ENTs) treats conditions involving the throat, tonsils, sinuses ears, mouth, head, and neck.

Podiatrists treat conditions affecting feet, ankles, and related structure of the legs.

Proctologists or colorectal surgeons specialize in diseases and conditions of the lower digestive tract, including the anus, colon, and rectum.

Pulmonologists treat conditions related to breathing functions of the lungs and heart.

Rheumatologists treat rheumatic and autoimmune conditions affecting the bones, joints, tendons, and muscles.

Urologists treat conditions of the urinary tract and also care for male reproductive health.

For a more comprehensive list of specialists go to the HHP List of specialists.

Types of Primary Care Providers

Primary Care Providers (PCPs) are often the first to diagnose and treat medical problems that affect adults. They also identify risk factors for disease and offer advice on prevention.

Primary care providers (PCP) provide health care on an as-needed and long-term basis for people in early adulthood through older age. PCPs are often the first to diagnose and treat medical problems that affect adults. They also identify risk factors for disease and offer advice on prevention. General services that primary care clinicians provide include:

perform age-appropriate periodic wellness assessments

prescribe medications

treat illnesses and injuries

screen for common health issues based on personal risk factors and family history

manage acute and chronic conditions

order diagnostic tests

make referrals to specialty clinicians when necessary

A PCP may be one of the following types:

Medical Doctors (MD) or Doctors of Osteopathy (DO) may also be called Internal Medicine Doctors.

Nurse Practitioners (NP) provide primary care independently or in conjunction with/under supervision of a physician (varies depending on state regulations).

Family Practice physicians can treat all age ranges within a family, asservices include pediatric and OB/GYN care.

Supporting health care professionals that provide care under the supervision of MD, DO, or NP:

Physician Assistants (PA) are licensed medical professionals that provide many of the same services as primary care physicians. PAs can examine, diagnose, and treat patients and are able to assist in minor procedures. PAs are also able to prescribe medications.

Nurses (RN, LPN, APRN) assist PCPs by delivering specified types of patient care and implementing treatment plans such as administering medications. Nurses are unable to prescribe medications.

Medical Assistant (MA) complete both administrative and clinical tasks in hospitals, physician offices, and other healthcare facilities. Their tasks can include taking medicals histories, preparing patients for examinations, and explaining procedures.

More information is available from the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Guardianship for Autistic Adults

Some people with autism make their own health care and medical decisions. Others cannot or prefer to have someone help them with these decisions. When health care matters are complex...

Some people with autism make their own health care and medical decisions. Others cannot or prefer to have someone help them with these decisions. When health care matters are complex or overwhelming it might be necessary to appoint a guardian. A health care guardian has the legal right to make health care decisions for another person, with full permission to access records and communicate with providers. A health care guardian may also be called a medical guardian.

Who should consider a health care guardian?

Caregivers for people with autism who interact with their clinicians are often required to become guardians so that they can do things like make appointments, access medical records and make important decisions in an emergency. A family with an autistic person should consider guardianship if there’s difficulty with at least one area of life:

Health care: The person cannot understand, communicate and decide about their own health care.

Food and shelter: The person cannot manage money, provide their own food or place to live.

Potential for exploitation, serious injury or illness: The person cannot consistently make decisions that help them stay safe.

Whenever possible, guardians are obligated to give their autistic family member a chance to understand and weigh in on all decisions.

Lisa Nowinsky, PhD, title, discusses guardianship and medical decision making for autistic adults:

Lisa Nowinski, PhD, Director of Non-Clinician Service, MGH Lurie Center for Autism

Health care guardians and other options for autistic adults

There are several options to consider when it comes to seeking guidance for medical decision-making. They may:

Request permission for someone to see their medical information and help with decisions.

Patients must give written permission for a family member to see their health information or help with decisions. Doctors have medical release forms in their offices or on their patient portals.

Use a tool called Supported Decision Making.Supported Decision Making is a way of seeking help with complex medical decisions. The final decision lies with the patient, but they can bring other people (family, friends, support professionals, or other clinicians on their care team) into the conversation so that they make an informed choice.

Self-advocates who do not need a guardian can learn more about the kinds of support they can get from the American Civil Liberties Union’s FAQs on Supported Decision-Making.

Full guardianship.Guardianship is a legal process that often requires a lawyer, and each state has its own rules and may even have different types of guardians – it’s important to review the criteria for the state in which the autistic person lives. Legal forms are available at state government websites.

An attorney at Autism Spectrum News provides more details: Legal Guardianship: The Pros and Cons for Your Adult Disabled Child

Once guardianship is established, there are requirements for keeping it in place, usually an annual report filed in probate court (no lawyer required for that). Guardians should have proof of guardianship with them at all medical appointments and anywhere medical decisions are made. It’s a good idea to keep a copy of proof of guardianship (usually the court document awarding guardianship) in the car, backpack or purse.

Up for discussion

Guardianship decisions and the rules governing them are under review in many states as autistic self-advocates raise concerns about their right to make their own decisions. The National Council on Disability’s report Turning Rights into Reality: How Guardianship and Alternatives Impact the Autonomy of People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities provides useful information about the changing attitudes and legislative initiatives affecting guardianship.

Communication Strategies

Communicating About Pain

Autistic people often find that when they feel pain they can’t explain it or locate the source of it as easily as most neurotypical people can.

In the past, some clinicians believed autistic people do not feel pain the way neurotypical people do, which was to say they thought that people who could not verbally communicate about their pain not feeling pain. We now know this isn’t true. Autistic people often find that when they feel pain they can’t explain it or locate the source of it as easily as most neurotypical people can.

Some autistic people may be more sensitive to pain than their neurotypical peers. This can be especially true for girls and women who have autism. This is why talking about pain is one of the most critical conversations to have with a new provider, and it should happen before the first physical exam.

Behaviors that may indicate pain in non-verbal adults

It’s sometimes hard to distinguish between behaviors that indicate pain and those that seek to communicate another problem. Some of the common pain related behaviors are:

Aggression

Running, pacing, bolting

Jumping, stomping, thrashing

Self-injury, sometimes, but not always at the source of the pain (such as banging/hitting head when having GI pain)

Subtle or strong pinching or grabbing body part that source of pain

Sudden, exaggerated repetitive actions, like hand flapping or throat scratching

Twisting or irregular motions/positions to make accommodations for discomfort

Screaming

Ingestion (e.g. overeating, quickly ingesting food and drink, food avoidance, vomiting, mouthing or eating non-food items)

Crying

Withdraws or becomes very still

Checklist for talking to a clinician about pain

It can be helpful to carry a list of pain-related concern to appointments. It might include:

It hurts when people touch me without asking first.

The thought of feeling pain makes me very nervous.

If something will cause pain, please tell me ahead of time.

If something will cause pain, please give me medicine or treatment to help it hurt less.

Pain scares me.

I don’t like needles and need to know if there will be shots or blood draws that might be painful

Using a Pain Scale

If a medical appointment involves addressing pain as a problem or symptom, it may be helpful to use a tool known as a pain scale. Pain scales give patients a way to self-report their pain in a way that helps clinicians make an accurate evaluation and diagnosis of underlying health issues.

There are several kinds of pain scales:

One type of pain scale involves patients assigning a number between 1 and 10 to . One would be “no pain,” and 10 would be the worst pain imaginable.

A non-verbal pain scale for adults may also be used to help communicate about and identify the source and severity of pain. Karen Turner, OT and Patient Navigator at Massachusetts General Hospital, explains:

Karen Turner, OT, is a Patient navigator at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston

The Massachusetts General Hospital Patient Accommodations Care Plan is useful communication tool that allows patients and families to document important conditions and behaviors that clinicians should know, including pain.

More information

Neuroscience News on People with Autism Experience Pain at a Higher Intensity

Recent research on autism and pain in adults.

Sibling Relationships

Communication is key to building healthy relationships and smooth transitions among family members.

Brothers and sisters, or siblings, are often key players for autistic adults and their caregivers, especially during transitional times. Research shows that autistic people who have siblings develop better social skills as well as a built-in resilience.

If an autistic person has more than one sibling, they are likely to have a different relationship with each. For example, some siblings may be able to provide strong emotional support, while others may be better at helping with, or taking on, decisions about finances and care. These roles can evolve across the lifespan, so it’s important that siblings try and maintain positive communication — not only with the autistic adult, but with one another.

Unique family dynamics

As in any family, sibling relationships change over time, but there can be unique challenges for both the autistic adult and their siblings during different stages of life. For example, older siblings might feel a sense of responsibility toward their autistic sibling and feel tentative about building a life outside the family unit. Younger siblings gain independence and develop skills and relationships that lead them to surpass their older, developmentally delayed autistic sibling. When this happens, autistic adults may struggle with feeling abandoned or jealous when a younger sibling moves out, gets married, or has children, while siblings in turn can feel guilty about becoming more independent.

Navigating sibling milestones

The goal for caregivers is to encourage the autistic adult to accept and adapt to the changes in routine and family structures, to ensure that siblings feel empowered to build independent lives while maintaining family connections. It’s productive to have conversations with the autistic adult about sibling life milestones in advance, to the extent that it’s possible. For example, when siblings prepare to leave home, caregivers can address:

how daily routines will change

when siblings will come home or when family will visit them

whether a sibling’s space or room will stay the same or be used for something else

ways siblings can communicate regularly (email, letter, video call).

Caregivers can help siblings by encouraging and supporting their life choices outside of the family home and communicating regularly about any changes in care, employment supports, and living arrangements with their autistic sibling. Keeping siblings informed about specific and general caregiver responsibilities gives them a chance to consider what role they may feel comfortable playing during their autistic sibling’s later years.

Resources for siblings

As attuned as caregivers can be to the needs of all of their children, parents who did not grow up with an autistic sibling can’t always empathize or understand the impact of autism on siblings. For most siblings, autism has punctuated their entire childhood. Siblings often benefit from talking with other siblings of autistic people or speaking with a therapist familiar with the dynamics of families touched by autism.

Because anxiety and depression are more common among siblings of autistic people, it’s important to assure that support and care are readily available. For families of people whose autism includes challenging behaviors, Autism Speaks has a guide for siblings and a Q&A that addresses some of those issues.

Sibling roles as caregivers age

Just as setting expectations and arranging for visits and regular contact is key when siblings first leave home, communication becomes increasingly important as caregivers and autistic adults get older. Family gatherings and holidays can be stressful for siblings if it is assumed they will replicate childhood rituals or vacation in the same place every year. Siblings can assist in skillfully introducing new activities alongside longtime family traditions, which serves to lighten the load on caregivers and prepare for transitions of care.

Another key consideration for siblings is how to plan for the time when parents, caregivers, or guardians can no longer provide care or support for the autistic adult. This is especially challenging when an autistic adult still lives at home. Siblings need to understand what caregivers do day-to-day long before this transition occurs, so that they are prepared to make decisions about care and support when the time comes.

Some things to consider:

How well do the siblings get along with their autistic sibling?

How do the neurotypical siblings get along with each other?

Have siblings been made aware of financial arrangements for their autistic sibling?

Are siblings prepared to advocate for the autistic adult?

Do siblings understand the medical needs of the autistic adult?

Caregivers can create opportunities to discuss and answer these questions and incorporate them into plans as they approach later transitions.

Learn more

AAHR article on Family Support and Wraparound Services

The Profound Autism Alliance has a Sibling Action Network

Autism Speaks: A Sibling’s Guide to Autism

Autism Speaks Q&A: Supporting Siblings of Autistic Children with Aggressive Behaviors

How to Bring Adult Siblings Into an Autistic Brother’s Life by Susan Senator in Psychology Today

The Sibling Support Project has resources and trainings for siblings of people with developmental disabilities

Autism Spectrum News on Adult Sibling Support

The Autism Science Foundation has a site with multiple resources for siblings, Sam’s Sibs Stick Together

Navigating Grief and Loss: A Guide for Siblings of people with IDD

Next steps: Starting the Conversation: Future Planning and Siblings of People with IDD.

Dietary Plan Tool for Schools and Day Programs

Autistic adults with special dietary needs and behaviors around food can benefit from a form that outlines those needs and the best interventions for use at school or day programs.

Autistic adults with special dietary needs and behaviors around food can benefit from a form that outlines those needs and the best interventions for use at school or day programs. Many school districts have a similar form for the school nurse but that information doesn’t always follow the adult after they turn 22.

We’ve designed an easy-to-use template based on the dietary information school districts require.

The Language of Autism

The saying goes, “if you’ve met one person with autism...you’ve met one person with autism.” The breadth of experience of autism is vast, and we want to address autism in...

The saying goes, “if you’ve met one person with autism…you’ve met one person with autism.” The breadth of experience of autism is vast, and we want to address autism in a way that respects this. For example, self-advocates often find that referring to autism as a disorder is offensive, while the families of those with autism requiring more substantial support want it to be clear that their experience of neurodiversity is quite disabling and qualifies as a disorder.

The changing language around autism

The words we use to talk about autism are continuously changing and evolving. The more linear language, including terms such as high-, moderate-, and low-functioning, has generally fallen out of favor because these terms fail to communicate that autism is characterized by splintered skills. A person with limited verbal communication skills can have intellectual acuity and great empathy, while someone who is highly verbal can be emotionally dysregulated and have extremely narrow interests that make it difficult for them to navigate the world. Very often it’s been the verbal skills that have dictated the “functioning” label, which has led to the proper conclusion that it’s an unfair and outdated measure.

Diagnostic criteria and “labels”

The current DSM-5 Criteria widened the diagnostic umbrella by removing Asperger’s Syndrome as an official diagnosis. However, while removing Hans Asperger and his ties to Nazis and eugenics was the right thing to do, that leaves people who have embraced the “Aspie” label identity adrift. The neurodiversity movement has tried to address this, and has not only shifted the lens from a purely medical model to a more social model of disability, but it has also empowered many autistic people to embrace their neurodiversity and find community with like-minded peers. Many self-advocates now proudly claim to be neurodivergent or “neurospicy.” Proponents of the autistic-led neurodiversity movement consider autism as something to be celebrated while also recognizing their support needs.

At this writing, the DSM-5 lists three levels of autism that are determined not by a person’s specific abilities but by the level of support they require:

Level 1: requires support

Level 2: requires substantial support

Level 3: requires very substantial support

These categorizations are useful for doctors and other health care professionals. For those in the support and social communities, however, such labels can seem detached and “deficit” rather than “strength” focused. It is important to remember that labels can provide a framework with which to understand each other and ourselves. It can help an autistic person and their loved ones understand why they find some things so difficult, and also why they might excel in other areas.

Our language will evolve with yours

Many patients and families have generously agreed to appear on this site and in our clinical course and we’ve consulted with them in regard to language. We share these choices with humility, recognizing the importance of evolving the understanding of autism, how that is reflected in the language we use and what it means for individuals and families.

We use both person-first language (e.g., person with autism), as well as adjective-first language (e.g., autistic person) on this site. For some members of the autism community, using adjective-first language is preferable to signify a sense of identity rather than a more medicalized “condition.” We have taken some cues from the most up-to-date language recommendations available via the American Medical Association, which also informed the choices in our clinician course.

We at AAHR will revise and adapt the language on the site as best we can to meet the needs of everyone in the autism community. We may not always get it right the first time, but we will always do our best to honor the most respectful and inclusive language. Regardless of the language that we use on this site, the intent is always to incorporate wording that is accessible, inclusive, and reflective of the priorities of the autistic community.

Planning for Medical Emergencies

Everyone—autistic people and neurotypical people—can benefit from planning for medical or mental health emergencies.

Be ready: Make a 'Go Bag'

Emergencies are easier to handle if information and supplies are at the ready. Keeping a Go Bag near the door or in the car can help.

The Go Bag – a printable list of things to have on hand to help prepare for emergencies

Start by calling the PCP

Everyone—autistic people and neurotypical people—can benefit from planning for medical or mental health emergencies. If a trip to the emergency department (ED) is necessary, you’ll want to alert your primary care provider’s office (another person in the household can make this call as necessary). It’s especially helpful to request that the PCP call ahead and let the ED or hospital know that an autistic patient is on the way and they can share any pertinent information that can be helpful for your care.

Make a call tree

Another key part of the plan is to create a call tree that includes someone in the circle of support who can contact others who should be alerted to the emergency. This information should be clearly displayed in a prominent position in your home. This is especially important for first responders-police, fire, and EMS – in case you are alone during an emergency. The call tree contacts can include service provider or group home staff, neighbors who can assist with caring for others in the family, and extended family.

Register with the local police

Most local police departmetns have a way of registering citizens with special health needs. If there are details they should know about how autism presents in you or the adult in your family take a moment to communicate about those concerns. For example, some people panic and hide when they hear sirens, see someone in uniform, or even hear the doorbell.

Calling 911

Most clinicians’ offices direct people in crisis to the local emergency department or urgent care center. If calling 911 is the best or only option, clearly state to the dispatcher that the patient is a person with autism and let them know about any communication or behavioral challenges that might be misunderstood. Many first responders are trained to interact with autistic people but many are not – it’s important to know ahead if time if local police, fire, and EMS are trained in working with the autistic community. Autism Speaks has a guide for first responders that can be shared with local public safety organizations, including information for dispatchers. In addition, there are several programs that train first responders to safely interact with autistic people, including Autism Alert and Autism Risk and Safety Management.

Tips for interacting with first responders

Whether an emergency occurs in the home or out in the community, an autism ID can be useful. It can be a simple card with details that are specific to the individual and can help avoid misunderstandings in stressful situations. Caregivers can share an ID card or self-advocates can carry them and share as necessary.

The card be shared with first responders or with staff and clinicians in emergency departments, urgent care, and hospitals. There are Medicalert IDs for autism and also sites that can create an autism ID for a fee. This one was created using a free site called Canva:

A sample identification card that outlines what strategies autstic people can use to communicate in an emergency

Mental health emergencies

When there’s a mental health emergency, think carefully about what the goal is for taking someone to the Emergency Department. Dr. Robyn Thom, a psychiatrist at the MGH Lurie Center for Autism, discusses expectations for a mental health care visit to the Emergency Department:

Dr. Robyn Thom on things to consider when going to the emergency room for a mental health emergency.

A 3×5 identification card to print and use for communicating in an emergency

Successful Telehealth Appointments

Telehealth can help those who don’t live near an autism specialist or other care provider, or if it is difficult to go to appointments in person.

Some healthcare appointments don’t require an office visit and instead can take place via telehealth. Telehealth visits usually occur using a secure videoconference platform on a personal computer, tablet, or other mobile device.

Telehealth can be useful for some types of evaluations, such as a wellness check-in or certain parts of neuropsychological exams. Each provider will have specific guidelines about when a telehealth visit may be substituted for an in-person visit, so be sure to ask.

Does insurance pay for telehealth?

The rules about telehealth coverage have changed since the end of the pandemic emergency. Check with insurance providers to see which telehealth visits are covered. It is also a good idea to see if the provider plans to offer and bill for these visits over the long term.

Benefits of telehealth

A successful telehealth appointment depends on whether the patient and provider are both comfortable with the technology and don’t mind communicating remotely if a private, quiet space is accessible. Telehealth can help those who don’t live near an autism specialist or other care provider, or if it is difficult to go to appointments in person. Some benefits to patients include:

a home or familiar environment is less stressful compared with a clinical setting

fewer transitions involved like travel, wait times, and noisy spaces

avoiding the logistics, time, and cost of travel

it can be easier to include many members of the care team (clinicians, family members, and group home/provider staff).

Downsides of telehealth

Telehealth may not be a good choice if/when

A physical examination or in-person treatment is necessary

There’s a problem that is difficult to describe or see over video (e.g., abnormal movements)

Certain tests are required, such as blood draws

The patient is not comfortable communicating via video or by phone

The patient is inclined to get distracted or wander off when not engaging in person.

Keys to a good telehealth visit

Tips for a successful telehealth appointment:

Use a private, quiet indoor space — telehealth from a car (never a moving one!) should be for emergencies only.

Make sure there’s a strong, stable internet connection on the device.

Ideally, use a device with a stable camera that can stand alone — a tablet or desktop computer is preferable to a phone.

Two or three days before the appointment, test the video software, the internet connection, camera, and microphone to make sure everything is working and that video and sound are clear.

At the start of an appointment, give the provider a contact phone number in case the connection is lost.

While a caregiver may help with communication or give information to the clinician, the autistic adult should be available to appear on camera for as much of the visit as possible.

ECHO for Autism is a good resource for providers and patients to learn more about using telehealth to deliver care.

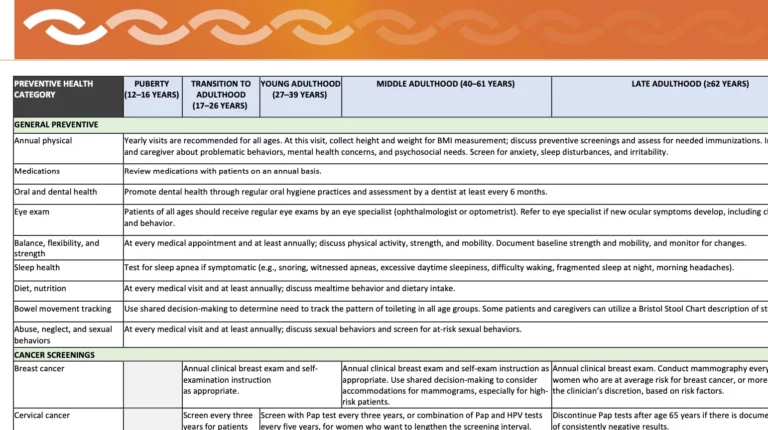

Useful Information about Preventive Care

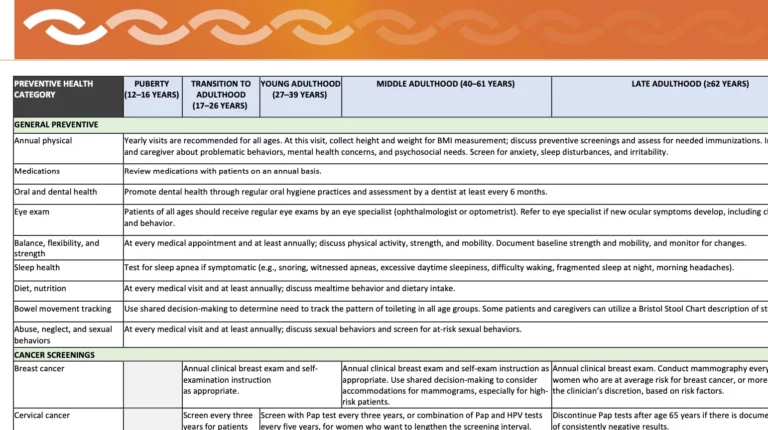

As part of its free course, Clinical Care for Autistic Adults, Harvard Medical School developed a useful time line for preventive health care screenings and immunizations for autistic adults.

This downloadable and printable Autism Preventive Health Table was developed as part of the Harvard Medical School’s course, Clinical Care for Autistic Adults. It lists baseline preventive health care screenings and immunizations for autistic adults. The intended audience is primary care physicians but feel free to use as a reference and to share with your PCPs or other providers. Key points for caregivers and self-advocates to note:

Schedule all annual exams well in advance so that the appointment happens at a time of year and time of day that works best for the patient/family.

If possible, gather information about health conditions that can run in families such as heart problems, cancer, diabetes, depression, and addiction. This information can help identify the most important screenings and how often they should be done.

A guide to share with providers for preventive health care

The information on the table is based on the following sources:

Adult Immunization Schedule by Age, CDC, 2023.

CDC: Cancer Screening Tests. Accessed on April 1, 2023.

Dhanasekara CS, Ancona D, Cortes L, et al. Association Between Autism Spectrum Disorders and Cardiometabolic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(3):248-257. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5629

Isenberg BM, Yule AM, McKowen JW, Nowinski LA, Forchelli GA, Wilens TE. Considerations for Treating Young People With Comorbid Autism Spectrum Disorder and Substance Use Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(12):1139-1141. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.08.467

Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services Adult Screening Recommendations 2019, Mass.gov.Accessed on April 1, 2023.

Schick, Elizabeth, Is It Safe to Sedate our Son at the Dentist? Autism Speaks. 2014. Accessed on April 1, 2023.

Screening and Preventive Interventions for Oral Health in Children 5 Years and Older and Adults, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed on April 1, 2023.

Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021, CDC. Accessed on April 1, 2023.

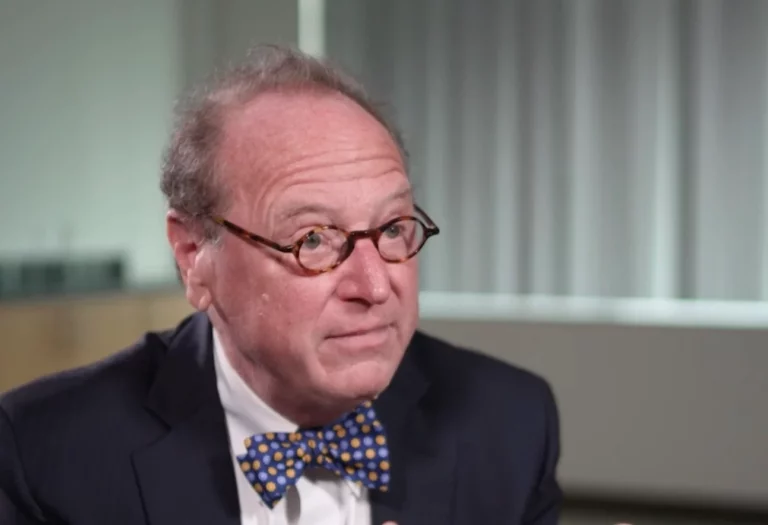

Dr. James Bath, a primary care physician for autistic adults at the MGH Lurie Center for Autism, discusses the importance of preventive care as key to a long, healthy life:

Dr. James Bath, Adult Primary Care Physician at the MGH Lurie Center for Autism

Patient Navigators

A patient navigator helps patients and clinicians create and access autism-competent care. They focus on improving processes for both inpatient and outpatient care in a medical facility and identify opportunities...

A patient navigator helps patients and clinicians create and access autism-competent care.

They focus on improving processes for both inpatient and outpatient care in a medical facility and identify opportunities to improve outreach so patients and staff are aware of the tools and resources that can improve care and outcomes. Some patient navigators specialize in assisting cancer patients but in the context of autism they work with providers to enhance their understanding of an autistic person’s unique communication, sensory, and behavioral needs.

Patient navigators also coordinate care and seek out opportunities to improve outreach in ways that heighten awareness of the specific needs that make healthcare more accessible and comfortable for autistic people.

While the work of a patient navigator is largely within the healthcare setting, they can also work with autistic adults to develop tools outside of the office environment to help with recovery from medical procedures and to assure continued good health. Such supports could include physical exercise or accommodations at home to help with mobility, guides for personal care, or communication tools for working with physical therapists.

Meet Karen Turner