Clear all filters

Communication Strategies

Sibling Relationships

Communication is key to building healthy relationships and smooth transitions among family members.

Brothers and sisters, or siblings, are often key players for autistic adults and their caregivers, especially during transitional times. Research shows that autistic people who have siblings develop better social skills as well as a built-in resilience.

If an autistic person has more than one sibling, they are likely to have a different relationship with each. For example, some siblings may be able to provide strong emotional support, while others may be better at helping with, or taking on, decisions about finances and care. These roles can evolve across the lifespan, so it’s important that siblings try and maintain positive communication — not only with the autistic adult, but with one another.

Unique family dynamics

As in any family, sibling relationships change over time, but there can be unique challenges for both the autistic adult and their siblings during different stages of life. For example, older siblings might feel a sense of responsibility toward their autistic sibling and feel tentative about building a life outside the family unit. Younger siblings gain independence and develop skills and relationships that lead them to surpass their older, developmentally delayed autistic sibling. When this happens, autistic adults may struggle with feeling abandoned or jealous when a younger sibling moves out, gets married, or has children, while siblings in turn can feel guilty about becoming more independent.

Navigating sibling milestones

The goal for caregivers is to encourage the autistic adult to accept and adapt to the changes in routine and family structures, to ensure that siblings feel empowered to build independent lives while maintaining family connections. It’s productive to have conversations with the autistic adult about sibling life milestones in advance, to the extent that it’s possible. For example, when siblings prepare to leave home, caregivers can address:

how daily routines will change

when siblings will come home or when family will visit them

whether a sibling’s space or room will stay the same or be used for something else

ways siblings can communicate regularly (email, letter, video call).

Caregivers can help siblings by encouraging and supporting their life choices outside of the family home and communicating regularly about any changes in care, employment supports, and living arrangements with their autistic sibling. Keeping siblings informed about specific and general caregiver responsibilities gives them a chance to consider what role they may feel comfortable playing during their autistic sibling’s later years.

Resources for siblings

As attuned as caregivers can be to the needs of all of their children, parents who did not grow up with an autistic sibling can’t always empathize or understand the impact of autism on siblings. For most siblings, autism has punctuated their entire childhood. Siblings often benefit from talking with other siblings of autistic people or speaking with a therapist familiar with the dynamics of families touched by autism.

Because anxiety and depression are more common among siblings of autistic people, it’s important to assure that support and care are readily available. For families of people whose autism includes challenging behaviors, Autism Speaks has a guide for siblings and a Q&A that addresses some of those issues.

Sibling roles as caregivers age

Just as setting expectations and arranging for visits and regular contact is key when siblings first leave home, communication becomes increasingly important as caregivers and autistic adults get older. Family gatherings and holidays can be stressful for siblings if it is assumed they will replicate childhood rituals or vacation in the same place every year. Siblings can assist in skillfully introducing new activities alongside longtime family traditions, which serves to lighten the load on caregivers and prepare for transitions of care.

Another key consideration for siblings is how to plan for the time when parents, caregivers, or guardians can no longer provide care or support for the autistic adult. This is especially challenging when an autistic adult still lives at home. Siblings need to understand what caregivers do day-to-day long before this transition occurs, so that they are prepared to make decisions about care and support when the time comes.

Some things to consider:

How well do the siblings get along with their autistic sibling?

How do the neurotypical siblings get along with each other?

Have siblings been made aware of financial arrangements for their autistic sibling?

Are siblings prepared to advocate for the autistic adult?

Do siblings understand the medical needs of the autistic adult?

Caregivers can create opportunities to discuss and answer these questions and incorporate them into plans as they approach later transitions.

Learn more

AAHR article on Family Support and Wraparound Services

The Profound Autism Alliance has a Sibling Action Network

Autism Speaks: A Sibling’s Guide to Autism

Autism Speaks Q&A: Supporting Siblings of Autistic Children with Aggressive Behaviors

How to Bring Adult Siblings Into an Autistic Brother’s Life by Susan Senator in Psychology Today

The Sibling Support Project has resources and trainings for siblings of people with developmental disabilities

Autism Spectrum News on Adult Sibling Support

The Autism Science Foundation has a site with multiple resources for siblings, Sam’s Sibs Stick Together

Navigating Grief and Loss: A Guide for Siblings of people with IDD

Next steps: Starting the Conversation: Future Planning and Siblings of People with IDD.

Communicating About Pain

Autistic people often find that when they feel pain they can’t explain it or locate the source of it as easily as most neurotypical people can.

In the past, some clinicians believed autistic people do not feel pain the way neurotypical people do, which was to say they thought that people who could not verbally communicate about their pain not feeling pain. We now know this isn’t true. Autistic people often find that when they feel pain they can’t explain it or locate the source of it as easily as most neurotypical people can.

Some autistic people may be more sensitive to pain than their neurotypical peers. This can be especially true for girls and women who have autism. This is why talking about pain is one of the most critical conversations to have with a new provider, and it should happen before the first physical exam.

Behaviors that may indicate pain in non-verbal adults

It’s sometimes hard to distinguish between behaviors that indicate pain and those that seek to communicate another problem. Some of the common pain related behaviors are:

Aggression

Running, pacing, bolting

Jumping, stomping, thrashing

Self-injury, sometimes, but not always at the source of the pain (such as banging/hitting head when having GI pain)

Subtle or strong pinching or grabbing body part that source of pain

Sudden, exaggerated repetitive actions, like hand flapping or throat scratching

Twisting or irregular motions/positions to make accommodations for discomfort

Screaming

Ingestion (e.g. overeating, quickly ingesting food and drink, food avoidance, vomiting, mouthing or eating non-food items)

Crying

Withdraws or becomes very still

Checklist for talking to a clinician about pain

It can be helpful to carry a list of pain-related concern to appointments. It might include:

It hurts when people touch me without asking first.

The thought of feeling pain makes me very nervous.

If something will cause pain, please tell me ahead of time.

If something will cause pain, please give me medicine or treatment to help it hurt less.

Pain scares me.

I don’t like needles and need to know if there will be shots or blood draws that might be painful

Using a Pain Scale

If a medical appointment involves addressing pain as a problem or symptom, it may be helpful to use a tool known as a pain scale. Pain scales give patients a way to self-report their pain in a way that helps clinicians make an accurate evaluation and diagnosis of underlying health issues.

There are several kinds of pain scales:

One type of pain scale involves patients assigning a number between 1 and 10 to . One would be “no pain,” and 10 would be the worst pain imaginable.

A non-verbal pain scale for adults may also be used to help communicate about and identify the source and severity of pain. Karen Turner, OT and Patient Navigator at Massachusetts General Hospital, explains:

Karen Turner, OT, is a Patient navigator at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston

The Massachusetts General Hospital Patient Accommodations Care Plan is useful communication tool that allows patients and families to document important conditions and behaviors that clinicians should know, including pain.

More information

Neuroscience News on People with Autism Experience Pain at a Higher Intensity

Recent research on autism and pain in adults.

Useful Information about Preventive Care

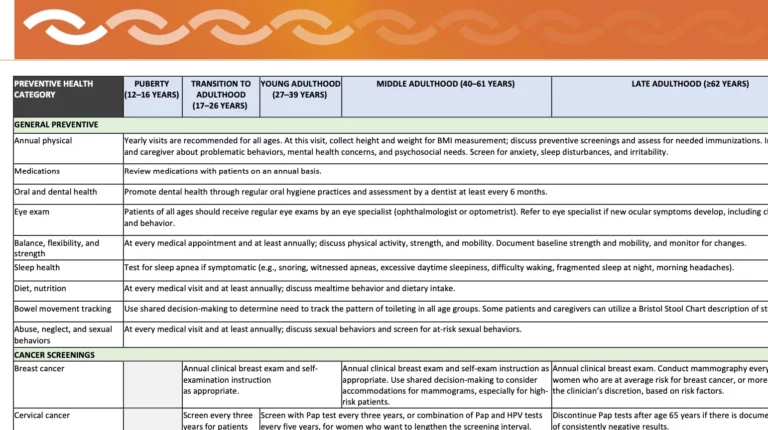

As part of its free course, Clinical Care for Autistic Adults, Harvard Medical School developed a useful time line for preventive health care screenings and immunizations for autistic adults.

This downloadable and printable Autism Preventive Health Table was developed as part of the Harvard Medical School’s course, Clinical Care for Autistic Adults. It lists baseline preventive health care screenings and immunizations for autistic adults. The intended audience is primary care physicians but feel free to use as a reference and to share with your PCPs or other providers. Key points for caregivers and self-advocates to note:

Schedule all annual exams well in advance so that the appointment happens at a time of year and time of day that works best for the patient/family.

If possible, gather information about health conditions that can run in families such as heart problems, cancer, diabetes, depression, and addiction. This information can help identify the most important screenings and how often they should be done.

A guide to share with providers for preventive health care

The information on the table is based on the following sources:

Adult Immunization Schedule by Age, CDC, 2023.

CDC: Cancer Screening Tests. Accessed on April 1, 2023.

Dhanasekara CS, Ancona D, Cortes L, et al. Association Between Autism Spectrum Disorders and Cardiometabolic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(3):248-257. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5629

Isenberg BM, Yule AM, McKowen JW, Nowinski LA, Forchelli GA, Wilens TE. Considerations for Treating Young People With Comorbid Autism Spectrum Disorder and Substance Use Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(12):1139-1141. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.08.467

Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services Adult Screening Recommendations 2019, Mass.gov.Accessed on April 1, 2023.

Schick, Elizabeth, Is It Safe to Sedate our Son at the Dentist? Autism Speaks. 2014. Accessed on April 1, 2023.

Screening and Preventive Interventions for Oral Health in Children 5 Years and Older and Adults, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed on April 1, 2023.

Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021, CDC. Accessed on April 1, 2023.

Dr. James Bath, a primary care physician for autistic adults at the MGH Lurie Center for Autism, discusses the importance of preventive care as key to a long, healthy life:

Dr. James Bath, Adult Primary Care Physician at the MGH Lurie Center for Autism

Successful Telehealth Appointments

Telehealth can help those who don’t live near an autism specialist or other care provider, or if it is difficult to go to appointments in person.

Some healthcare appointments don’t require an office visit and instead can take place via telehealth. Telehealth visits usually occur using a secure videoconference platform on a personal computer, tablet, or other mobile device.

Telehealth can be useful for some types of evaluations, such as a wellness check-in or certain parts of neuropsychological exams. Each provider will have specific guidelines about when a telehealth visit may be substituted for an in-person visit, so be sure to ask.

Does insurance pay for telehealth?

The rules about telehealth coverage have changed since the end of the pandemic emergency. Check with insurance providers to see which telehealth visits are covered. It is also a good idea to see if the provider plans to offer and bill for these visits over the long term.

Benefits of telehealth

A successful telehealth appointment depends on whether the patient and provider are both comfortable with the technology and don’t mind communicating remotely if a private, quiet space is accessible. Telehealth can help those who don’t live near an autism specialist or other care provider, or if it is difficult to go to appointments in person. Some benefits to patients include:

a home or familiar environment is less stressful compared with a clinical setting

fewer transitions involved like travel, wait times, and noisy spaces

avoiding the logistics, time, and cost of travel

it can be easier to include many members of the care team (clinicians, family members, and group home/provider staff).

Downsides of telehealth

Telehealth may not be a good choice if/when

A physical examination or in-person treatment is necessary

There’s a problem that is difficult to describe or see over video (e.g., abnormal movements)

Certain tests are required, such as blood draws

The patient is not comfortable communicating via video or by phone

The patient is inclined to get distracted or wander off when not engaging in person.

Keys to a good telehealth visit

Tips for a successful telehealth appointment:

Use a private, quiet indoor space — telehealth from a car (never a moving one!) should be for emergencies only.

Make sure there’s a strong, stable internet connection on the device.

Ideally, use a device with a stable camera that can stand alone — a tablet or desktop computer is preferable to a phone.

Two or three days before the appointment, test the video software, the internet connection, camera, and microphone to make sure everything is working and that video and sound are clear.

At the start of an appointment, give the provider a contact phone number in case the connection is lost.

While a caregiver may help with communication or give information to the clinician, the autistic adult should be available to appear on camera for as much of the visit as possible.

ECHO for Autism is a good resource for providers and patients to learn more about using telehealth to deliver care.

The Language of Autism

The saying goes, “if you’ve met one person with autism...you’ve met one person with autism.” The breadth of experience of autism is vast, and we want to address autism in...

The saying goes, “if you’ve met one person with autism…you’ve met one person with autism.” The breadth of experience of autism is vast, and we want to address autism in a way that respects this. For example, self-advocates often find that referring to autism as a disorder is offensive, while the families of those with autism requiring more substantial support want it to be clear that their experience of neurodiversity is quite disabling and qualifies as a disorder.

The changing language around autism

The words we use to talk about autism are continuously changing and evolving. The more linear language, including terms such as high-, moderate-, and low-functioning, has generally fallen out of favor because these terms fail to communicate that autism is characterized by splintered skills. A person with limited verbal communication skills can have intellectual acuity and great empathy, while someone who is highly verbal can be emotionally dysregulated and have extremely narrow interests that make it difficult for them to navigate the world. Very often it’s been the verbal skills that have dictated the “functioning” label, which has led to the proper conclusion that it’s an unfair and outdated measure.

Diagnostic criteria and “labels”

The current DSM-5 Criteria widened the diagnostic umbrella by removing Asperger’s Syndrome as an official diagnosis. However, while removing Hans Asperger and his ties to Nazis and eugenics was the right thing to do, that leaves people who have embraced the “Aspie” label identity adrift. The neurodiversity movement has tried to address this, and has not only shifted the lens from a purely medical model to a more social model of disability, but it has also empowered many autistic people to embrace their neurodiversity and find community with like-minded peers. Many self-advocates now proudly claim to be neurodivergent or “neurospicy.” Proponents of the autistic-led neurodiversity movement consider autism as something to be celebrated while also recognizing their support needs.

At this writing, the DSM-5 lists three levels of autism that are determined not by a person’s specific abilities but by the level of support they require:

Level 1: requires support

Level 2: requires substantial support

Level 3: requires very substantial support

These categorizations are useful for doctors and other health care professionals. For those in the support and social communities, however, such labels can seem detached and “deficit” rather than “strength” focused. It is important to remember that labels can provide a framework with which to understand each other and ourselves. It can help an autistic person and their loved ones understand why they find some things so difficult, and also why they might excel in other areas.

Our language will evolve with yours

Many patients and families have generously agreed to appear on this site and in our clinical course and we’ve consulted with them in regard to language. We share these choices with humility, recognizing the importance of evolving the understanding of autism, how that is reflected in the language we use and what it means for individuals and families.

We use both person-first language (e.g., person with autism), as well as adjective-first language (e.g., autistic person) on this site. For some members of the autism community, using adjective-first language is preferable to signify a sense of identity rather than a more medicalized “condition.” We have taken some cues from the most up-to-date language recommendations available via the American Medical Association, which also informed the choices in our clinician course.

We at AAHR will revise and adapt the language on the site as best we can to meet the needs of everyone in the autism community. We may not always get it right the first time, but we will always do our best to honor the most respectful and inclusive language. Regardless of the language that we use on this site, the intent is always to incorporate wording that is accessible, inclusive, and reflective of the priorities of the autistic community.

Planning for Medical Emergencies

Everyone—autistic people and neurotypical people—can benefit from planning for medical or mental health emergencies.

Be ready: Make a 'Go Bag'

Emergencies are easier to handle if information and supplies are at the ready. Keeping a Go Bag near the door or in the car can help.

The Go Bag – a printable list of things to have on hand to help prepare for emergencies

Start by calling the PCP

Everyone—autistic people and neurotypical people—can benefit from planning for medical or mental health emergencies. If a trip to the emergency department (ED) is necessary, you’ll want to alert your primary care provider’s office (another person in the household can make this call as necessary). It’s especially helpful to request that the PCP call ahead and let the ED or hospital know that an autistic patient is on the way and they can share any pertinent information that can be helpful for your care.

Make a call tree

Another key part of the plan is to create a call tree that includes someone in the circle of support who can contact others who should be alerted to the emergency. This information should be clearly displayed in a prominent position in your home. This is especially important for first responders-police, fire, and EMS – in case you are alone during an emergency. The call tree contacts can include service provider or group home staff, neighbors who can assist with caring for others in the family, and extended family.

Register with the local police

Most local police departmetns have a way of registering citizens with special health needs. If there are details they should know about how autism presents in you or the adult in your family take a moment to communicate about those concerns. For example, some people panic and hide when they hear sirens, see someone in uniform, or even hear the doorbell.

Calling 911

Most clinicians’ offices direct people in crisis to the local emergency department or urgent care center. If calling 911 is the best or only option, clearly state to the dispatcher that the patient is a person with autism and let them know about any communication or behavioral challenges that might be misunderstood. Many first responders are trained to interact with autistic people but many are not – it’s important to know ahead if time if local police, fire, and EMS are trained in working with the autistic community. Autism Speaks has a guide for first responders that can be shared with local public safety organizations, including information for dispatchers. In addition, there are several programs that train first responders to safely interact with autistic people, including Autism Alert and Autism Risk and Safety Management.

Tips for interacting with first responders

Whether an emergency occurs in the home or out in the community, an autism ID can be useful. It can be a simple card with details that are specific to the individual and can help avoid misunderstandings in stressful situations. Caregivers can share an ID card or self-advocates can carry them and share as necessary.

The card be shared with first responders or with staff and clinicians in emergency departments, urgent care, and hospitals. There are Medicalert IDs for autism and also sites that can create an autism ID for a fee. This one was created using a free site called Canva:

A sample identification card that outlines what strategies autstic people can use to communicate in an emergency

Mental health emergencies

When there’s a mental health emergency, think carefully about what the goal is for taking someone to the Emergency Department. Dr. Robyn Thom, a psychiatrist at the MGH Lurie Center for Autism, discusses expectations for a mental health care visit to the Emergency Department:

Dr. Robyn Thom on things to consider when going to the emergency room for a mental health emergency.

A 3×5 identification card to print and use for communicating in an emergency

Dietary Plan Tool for Schools and Day Programs

Autistic adults with special dietary needs and behaviors around food can benefit from a form that outlines those needs and the best interventions for use at school or day programs.

Autistic adults with special dietary needs and behaviors around food can benefit from a form that outlines those needs and the best interventions for use at school or day programs. Many school districts have a similar form for the school nurse but that information doesn’t always follow the adult after they turn 22.

We’ve designed an easy-to-use template based on the dietary information school districts require.

Patient Navigators

A patient navigator helps patients and clinicians create and access autism-competent care. They focus on improving processes for both inpatient and outpatient care in a medical facility and identify opportunities...

A patient navigator helps patients and clinicians create and access autism-competent care.

They focus on improving processes for both inpatient and outpatient care in a medical facility and identify opportunities to improve outreach so patients and staff are aware of the tools and resources that can improve care and outcomes. Some patient navigators specialize in assisting cancer patients but in the context of autism they work with providers to enhance their understanding of an autistic person’s unique communication, sensory, and behavioral needs.

Patient navigators also coordinate care and seek out opportunities to improve outreach in ways that heighten awareness of the specific needs that make healthcare more accessible and comfortable for autistic people.

While the work of a patient navigator is largely within the healthcare setting, they can also work with autistic adults to develop tools outside of the office environment to help with recovery from medical procedures and to assure continued good health. Such supports could include physical exercise or accommodations at home to help with mobility, guides for personal care, or communication tools for working with physical therapists.

Meet Karen Turner

Karen Turner is a patient navigator at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, MA, and has developed tools and strategies for autistic people that have vastly improved the health outcomes for people with some of the most challenging forms of autism. She emphasizes the importance of creativity and flexibility in building in accommodations for autistic people and notes that she has ‘never seen an unreasonable accommodation’ for someone with autism.

Check the local hospital or clinic website to see if they list a patient navigator. While not every medical facility hospital has one it’s always wise to ask hospitals who on their staff is designated to help people with sensory needs, intellectual disabilities or communication challenges get the care they deserve. Many hospitals have clinical social workers who can be helpful in some of the same ways. Asking for accommodations is a form of advocacy and reinforces the need for these types of support staff positions to improve high quality care for autistic patients.

In this video, Karen gives advice about choosing a medical specialist.

Karen Turner, Patient Navigator at Massachusetts General Hospital, on choosing a medical specialist