Clear all filters

Care Transitions

Sibling Relationships

Communication is key to building healthy relationships and smooth transitions among family members.

Brothers and sisters, or siblings, are often key players for autistic adults and their caregivers, especially during transitional times. Research shows that autistic people who have siblings develop better social skills as well as a built-in resilience.

If an autistic person has more than one sibling, they are likely to have a different relationship with each. For example, some siblings may be able to provide strong emotional support, while others may be better at helping with, or taking on, decisions about finances and care. These roles can evolve across the lifespan, so it’s important that siblings try and maintain positive communication — not only with the autistic adult, but with one another.

Unique family dynamics

As in any family, sibling relationships change over time, but there can be unique challenges for both the autistic adult and their siblings during different stages of life. For example, older siblings might feel a sense of responsibility toward their autistic sibling and feel tentative about building a life outside the family unit. Younger siblings gain independence and develop skills and relationships that lead them to surpass their older, developmentally delayed autistic sibling. When this happens, autistic adults may struggle with feeling abandoned or jealous when a younger sibling moves out, gets married, or has children, while siblings in turn can feel guilty about becoming more independent.

Navigating sibling milestones

The goal for caregivers is to encourage the autistic adult to accept and adapt to the changes in routine and family structures, to ensure that siblings feel empowered to build independent lives while maintaining family connections. It’s productive to have conversations with the autistic adult about sibling life milestones in advance, to the extent that it’s possible. For example, when siblings prepare to leave home, caregivers can address:

how daily routines will change

when siblings will come home or when family will visit them

whether a sibling’s space or room will stay the same or be used for something else

ways siblings can communicate regularly (email, letter, video call).

Caregivers can help siblings by encouraging and supporting their life choices outside of the family home and communicating regularly about any changes in care, employment supports, and living arrangements with their autistic sibling. Keeping siblings informed about specific and general caregiver responsibilities gives them a chance to consider what role they may feel comfortable playing during their autistic sibling’s later years.

Resources for siblings

As attuned as caregivers can be to the needs of all of their children, parents who did not grow up with an autistic sibling can’t always empathize or understand the impact of autism on siblings. For most siblings, autism has punctuated their entire childhood. Siblings often benefit from talking with other siblings of autistic people or speaking with a therapist familiar with the dynamics of families touched by autism.

Because anxiety and depression are more common among siblings of autistic people, it’s important to assure that support and care are readily available. For families of people whose autism includes challenging behaviors, Autism Speaks has a guide for siblings and a Q&A that addresses some of those issues.

Sibling roles as caregivers age

Just as setting expectations and arranging for visits and regular contact is key when siblings first leave home, communication becomes increasingly important as caregivers and autistic adults get older. Family gatherings and holidays can be stressful for siblings if it is assumed they will replicate childhood rituals or vacation in the same place every year. Siblings can assist in skillfully introducing new activities alongside longtime family traditions, which serves to lighten the load on caregivers and prepare for transitions of care.

Another key consideration for siblings is how to plan for the time when parents, caregivers, or guardians can no longer provide care or support for the autistic adult. This is especially challenging when an autistic adult still lives at home. Siblings need to understand what caregivers do day-to-day long before this transition occurs, so that they are prepared to make decisions about care and support when the time comes.

Some things to consider:

How well do the siblings get along with their autistic sibling?

How do the neurotypical siblings get along with each other?

Have siblings been made aware of financial arrangements for their autistic sibling?

Are siblings prepared to advocate for the autistic adult?

Do siblings understand the medical needs of the autistic adult?

Caregivers can create opportunities to discuss and answer these questions and incorporate them into plans as they approach later transitions.

Learn more

AAHR article on Family Support and Wraparound Services

The Profound Autism Alliance has a Sibling Action Network

Autism Speaks: A Sibling’s Guide to Autism

Autism Speaks Q&A: Supporting Siblings of Autistic Children with Aggressive Behaviors

How to Bring Adult Siblings Into an Autistic Brother’s Life by Susan Senator in Psychology Today

The Sibling Support Project has resources and trainings for siblings of people with developmental disabilities

Autism Spectrum News on Adult Sibling Support

The Autism Science Foundation has a site with multiple resources for siblings, Sam’s Sibs Stick Together

Navigating Grief and Loss: A Guide for Siblings of people with IDD

Next steps: Starting the Conversation: Future Planning and Siblings of People with IDD.

Finding Autism-Competent Health Care

Why do we call it “autism-competent health care” instead of “autism-friendly health care?” Because medical providers can be friendly but not understand the best way to treat autistic patients. It’s an education issue, not an attitude issue.

Why do we call it “autism-competent health care” instead of “autism-friendly health care?” Because medical providers can be friendly but not understand how best to care for autistic patients. It’s an education issue, not an attitude issue.

For autistic people, it can be easier to avoid seeking care because both the process and the medical environment itself are too overwhelming. This can be due to the distractions caused by sounds and lights in the clinic, verbal instructions that are too quick or unclear, touch during exams that feels uncomfortable, or procedures like blood draws that are extra painful. Making appointments, getting to the office, and navigating through the steps of an office visit can all prove difficult, too. AAHR provides help on all of these fronts and more.

Most providers who care for adults understand neurodiversity, but not all of them know best practices when it comes to treating adults with autism. Harvard Medical School has created a clinician course to bring providers important knowledge about caring for autistic adults. Yet, autistic patients need to find good care now.

Get more specifics in our article What’s an Autism-Competent Office?

Resources to Help Find Autism-Competent Care

ECHO Autism has a directory for finding clinicians trained in best practices for treating autistic children and adults.

Psychology Today has an excellent directory for finding therapists, many of whom provide autism-competent care.

The AASPIRE Toolkit is a good resource that can help patients find an adult provider who understands autism-competent care.

Got Transition? has many key resources to guide autistic young adults and their families through transitions in medical care. Their Implementation Guides are especially useful in navigating the medical transition to new providers.

Help Clinicians Learn to Provide Autism-Competent Care

While most healthcare professionals understand neurodiversity, many do not know best practices when it comes to caring for autistic adults. Harvard Medical School’s CME accredited course, Clinical Care for Autistic Adults, can fill this knowledge gap.

Share the link or the QR code for access to this training for those who care for adults. The course is free and open to anyone, including patients and caregivers.

Getting an Autism Diagnosis as an Adult

The increased awareness of autism and associated neurodivergent traits in adults has led many to seek testing and/or a diagnosis.

Autism is commonly associated with childhood, the assumption being that if a person is autistic they will have received that diagnosis when they were young. This is not always the case. Some adults struggle with the symptoms and challenges associated with autism but have never received a formal diagnosis.

The increased awareness of autism and associated neurodivergent traits in adults has led many to seek testing and/or a diagnosis. Adults often consider autism when a person in their family is diagnosed and they recognize autistic traits in themselves. Because autism was long assumed to be more common in boys and men, it has traditionally been underdiagnosed in girls and women, who may still find getting a diagnosis as an adult particularly challenging.

Who can diagnose autism in adults?

Adults seeking a formal diagnosis can consult with their primary care provider, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, or a social worker to understand how best to seek an evaluation. A psychiatrist (MD), psychologist (PhD), or neuropsychologist (PhD) usually makes the medical diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (a full neuropsychological evaluation is not required). A medical diagnosis is necessary, however, to apply for any disability benefits on the basis of an autism diagnosis.

In this video, Dr. Chris McDougle, Director of the Lurie Center for Autism, discusses the process of seeking an autism diagnosis as an adult.

Dr. Chris McDougle, Director of the MGH Lurie Center for Autism

Where to learn more about an adult diagnosis

The Association for Autism and Neurodiversity (AANE) has advice for adults seeking a diagnosis. They offer information on why a person might (or might not) want to seek a diagnosis, and what an ASD diagnosis as an adult means across the lifespan. The website also provides useful advice on finding resources for help and how to talk about being autistic with family, friends, and employers. AANE also has many online groups that provide support and a sense of community for neurodivergent adults, as well as for their caregivers and families, regardless of whether they have a formal autism diagnosis.

More resources

Autism Speaks Adult Diagnosis Tool Kit This resource explains the diagnostic process, has links to clinicians who can diagnose ASD, and provides other information useful to those considering pursuing a formal ASD diagnosis.

Formal Diagnostic Criteria for Autism The medical criteria that clinicians use to diagnose autism.

Making Sense of the Past as a Late-Diagnosed Autistic Adult by Katie Rose Guest Pryal in Psychology Today

After all these years I finally understand that there’s a scientific reason for the way I am different, and that I didn’t do anything wrong by being this way.

—Maggie C., autistic adult

What’s an Autism-Competent Office?

Environments with tight spaces, and lots of noise and/or people are challenging for all patients, but especially those with the sensory issues that come with being autistic.

Environments with tight spaces, and lots of noise and/or people are challenging for all patients, but especially those with the sensory issues that come with being autistic.

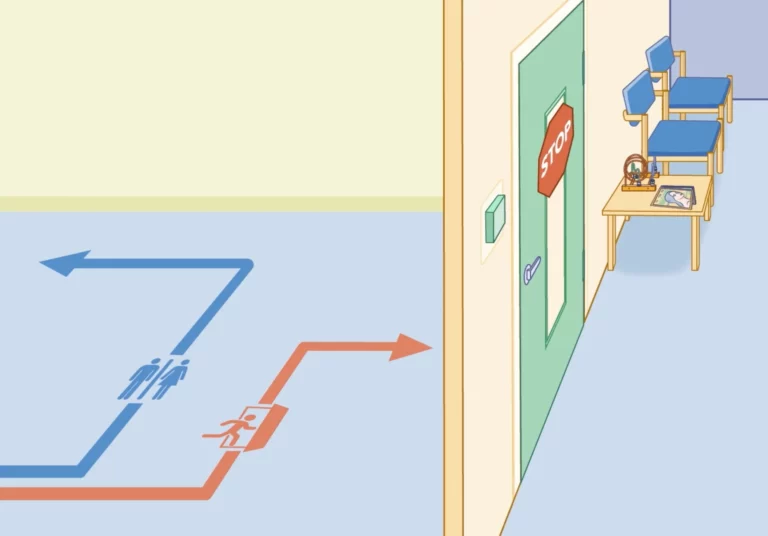

Some of the physical characteristics of an autism-competent clinical office or hospital include:

Fewer bright lights

A neat, orderly appearance, without too many magazines, video screens, or decorations

Quiet music and overhead sounds or none at all

Fewer smells from cleaning products or disinfectants

Calm neutral colors, keeping any areas of bright color to a minimum

Easy access to electrical outlets for keeping devices charged

Socially distanced seating

A quiet room or space separate from the waiting area

An autism-competent office or hospital offers more than one way to communicate between patients and staff. These may include:

Email

Online scheduling and access to medical records (also known as patient portals)

Texting

Phone calls and voicemail

A tablet or communication board for use during an appointment

Our Clinician Course, Clinical Care for Autistic Adults, gives healthcare providers advice on how to create autism-competent spaces and train clinical staff to better serve the needs of autistic patients. The downloadable tip sheet can help patients to advocate for autism-competent care while directing clinicians on how to best provide that care.

An innovative example of autism-competent, neurodiverse healthcare can be found at All Brains Belong, a medical practice that takes a “whole life” approach.

Animation: What’s an autism-competent medical office look like?

Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult Care

Transitioning from pediatric to adult care can be challenging as autistic patients outgrow the services of pediatric practices and enter a fragmented healthcare system that is less familiar.

It can be a challenging time as autistic patients leave the services of pediatric practices and enter a health care system for adults that is less familiar with their needs and less prepared to meet them. There’s no required age for this transition to happen, but it is usually between the ages of 18 and 22, and can happen as late as age 26. See our articles on insurance for more information about important decisions at ages 22 and 26.

Got Transition, a site focusing on health care transitions, is a valuable resource for families and self-advocates. It offers a readiness assessment tool, a transition timeline, and a robust frequently asked questions section.

There are a few key steps involved when transitioning from a pediatrician to an adult primary care provider (PCP).

Consider a “meet and greet” pre-appointment

For autistic people who require high levels of support, setting up an additional appointment when booking the patient’s first visit with their new PCP can be helpful. It can be reassuring for caregivers to meet alone with the PCP before the patient’s first visit to establish if the clinician is indeed a good fit. (Most insurance providers will cover this kind of consultation, but it’s always good to check.) Because the transition from pediatric to adult care often comes at a time when other big transitions are afoot, it may also be helpful to talk about any planned transitions from school to work or adult services either at the caregiver-clinician visit or at the first appointment.

As part of the HMS Clinician Course, Dr. James Bath, Primary Care Provider for Autistic Adults at the Lurie Center for Autism, helped to develop an Initial Visit Patient Profile form to facilitate a positive clinician-patient exchange of the key information during this transition.

Information to bring to a primary care visit

Transfer medical records

Once the new PCP is in place, it’s important to make sure that health care records are transferred to the new practice. Be sure to include specialist records as well as those from the pediatrician. These records should include all appointment notes as well as results of lab work, imaging, or other tests, so the new PCP has access to health history as well as current medical concerns.

Tips on transferring records:

Most clinicians use electronic health record (EHR) systems to store medical data, but sometimes different vendor systems are incompatible. It’s best to ask the receiving clinician’s office if there is anything you need to do on your end to facilitate a successful handoff.

Be sure to include records from specialists and evaluations such as neuropsychological reports (if these were completed through a school district, they will not be in the electronic medical record, but digital copies should be available from the provider).

If you’ve used a patient portal, download and keep copies of all records, as you will no longer have online access to this information once you leave a practice.

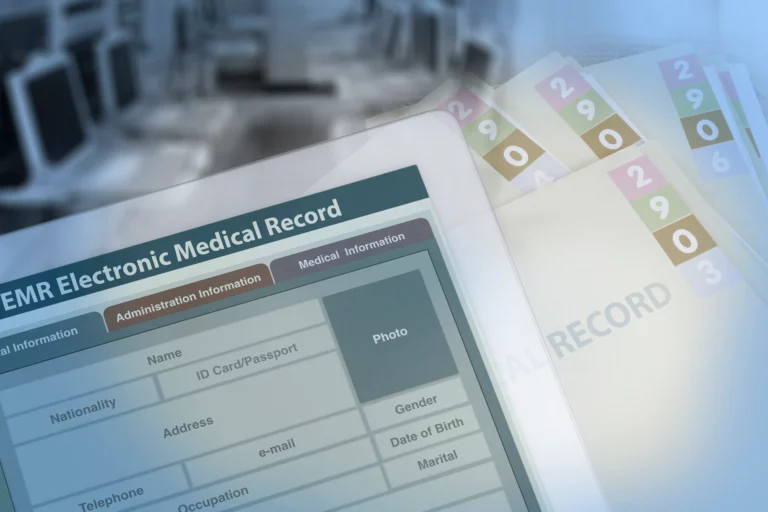

The difference between Electronic Medical Records (EMR) and Electronic Health Records (EHR)

Although the terms Electronic Medical Records (EMR) and Electronic Health Records (EHR) and are often used interchangeably, there are importance differences between them. EMRs are digital patient records and charts, while EHRs are that and more. EHRs are more comprehensive and include tools for prescribing medications electronically, ordering labs, streamlining internal and external communications, and sharing data.

Medication

Some things to keep in mind about medication:

Keep a list of all medication, dosage, instructions, and prescriber information and bring it to the first appointment. Keeping a master list will help to ensure that there are no missed doses during the transition process.

Discuss both current and past medication use with the PCP, including reasons for any past medication discontinuation, so a full medication history is clear.

Remember to pass along any new medication orders to care team members who distribute medication, such as day program providers, group home staff, teachers, therapists, or home care aides.

Dr. James Bath gives advice the transition from pediatric to adult care

Care team communication

Dr. Bath reinforces the value of communication during the transition from pediatric to adult care, and establishing a role as an essential part of the health care team. He notes that “The most integral part of having a successful health care transition is that we as the providers are listening to the families and the patients, and what their experiences have been and what has been successful and what has not been so successful, because that history is invaluable.”

During the first appointment, patients and caregivers should explain how they choose to be addressed, including preferred pronouns. Many people choose to be called by their first name or a nickname, while others opt for Mr., Miss, or Ms. The use of “Mom” and “Dad” might best be left behind in the pediatric office, and generalized terms may feel uncomfortable or condescending (for example, “pal” or “sweetie”). Personal identity and the terminology around it can be especially important for autistic self-advocates, so this is a key conversation.

Susan Senator, and AAHR subject expert and parents of an autistic adult, discusses the language of autism in Psychology Today, “Please don’t call my autistic son “Buddy.”

Like a general pediatrician, PCPs coordinate care across specialties, so it’s important to make sure they are aware of other clinicians providing care. That may or may not be clear through the medical record alone, so it can be helpful to have a list of names and contact information for all specialists and other providers on hand for the PCP.

Maura Sullivan, the parent of two autistic young men, understands the need for balance when communicating about health — that everyone needs to be part of the conversation and to participate in care in whatever way they are able.

As my kids transition, I want more of their voice to be heard and less of my voice to be heard

– Maura S.